We chose the hamlet of Beit Jeez in from the hundreds of Palestinian villages that were cleansed in 1948. Maryam was scouting locations for her film, and she was looking for a ’48 village where one scene in particular needed to be shot. It was the scene where the protagonist and his girlfriend go after robbing the bank, the place they hole up while they decide whether to continue going on with their crime spree, or to leave for good. It was important that it take place in the ruins of a ’48 village.

Her travels had taken her all around, from the areas around Umm al-Fahim in the triangle, to old villages in the plain between Acre and Haifa, to even the upper Galilee, to old hilltop villages overlooking the south of Lebanon. Once, in the village of Bir‘im where a Maronite church still stood partly intact, she’d found a group of women sitting, looking off into the distance. When she spoke to them, she realized from their accent that they were Lebanese. Talking with them, she found out they’d come with their families in 2000 when the Israeli occupation came to an end and could probably never go back. Now, they said, they lived in a nearby Palestinian Israeli village where no women would speak to them and where their husbands could find no work, not even with the IDF. The rest of their families lived in Jewish cities like Nahariya and Safad where they felt even more miserable and isolated. Many had already returned, though who knows what would be in store for those who did.

They often hitched a ride to the place on Fridays where they sat picnicking until sunset. They offered Maryam apples and sweet tea the day she was there. While she sat with them, they pointed out Mt. Meron, Mt. Hermon, the Golan, and even the faintest traces of the Shuf Mountains far to the North. Unfortunately, as compelling as these locations were, they didn’t feel right for the film. Maryam had so far had already seen more than 50 locations, she’d know the right one when it came along.

When she offered to give us a ride back from Tel Aviv, we were happy to tag along, since we’d always wanted to go along with her on one of her scouting expeditions. She got the name of the village from Walid Khalidi’s book, All That Remains. The entry on this village had a couple pictures, some history, and some indications of what remained. Of the villages in the region, Beit Jeez looked the most promising as a potential set. It was located in the plain around Latrun where serious fighting had taken place during the war. We read about the history of the fighting—Latrun was one of the places where residents had put up the most resistance, which is why it wasn’t captured during that war. Those nearby villages that put up resistance were punished severely when they were conquered. Beit Jeez was one such place, we read. The residents there had been given a day to take their possessions and leave. Then the Haganah demolished their houses, shops and mosque with carefully laid explosives. The book told us to expect to find only the old school and the remains of two adjoining houses.

It is one thing to read about a place in a book, but something else to find and see it for yourself. It is also difficult getting to know a landscape by working from the page. For one thing, the maps in the book did not match our road maps. For another, all the original names had been erased and replaced with Hebrew ones. We had to keep both maps open at the same time and figure out what the new name was, then find that and hope, when we got there that we’d find some of the landmarks described in the book. There were also problems of gauging spatial relationships: the maps used different scales, and the distances didn’t always correspond with those of the road. And then, of course, none of the road signs pointed to what we were looking for.

Our book told us to go to Har’el Kibbutz, which was near the rubble of the old village. As we approached, we spotted forests of Scotch pine arranged so deliberately that their planters never intended them to be anything but covering.

I remembered Oz telling us once that the thick, knotty roots of pines were especially effective at tearing apart stone walls and the remains of old foundations. Occasionally, we passed patches of prickly pear cactus, the famous sabra imported from Mexico centuries ago, which were another sure sign that there had been a Palestinian village here not long ago.

We decided to start looking in the forest. We turned off on a road that led to a lookout point, right in the middle of the park. At the top of the hill, we quickly found the schoolhouse, cracked, but amazingly still intact. Around and above stood a series of plaques and displays commemorating the Jewish soldiers killed in the area during the ’48 battles around Latrun. We counted more than 100 plaques in the parking lot itself. On one, we read about the tragic story of one brigade of Holocaust survivors. They’d been taken from the transit camps and brought to Palestine in boats, and then shipped off more or less directly to Latrun, where the fighting was at its worst. When they were pushed into the Jordanian tank corps, which at that moment was determined to hold the line, they were killed. Of course, the Arab armies were roundly defeated soon after, but for Israelis, the fighting at Latrun was mythical for its ferocity, heroism, and heartbreak. Everywhere we turned, there were plaques commemorating the event, and a very large, three-dimensional map to show how it transpired. We located our spot on the map and looked around, comparing it to the landscape around, comparing it to the maps we’d brought with us.

We soon wandered into the pines, and called out every time we located another old patch of prickly pear. But, aside from some old foundations whose outlines were too oblique to make much out of them, we found nothing in the forest. We walked back to the car, and noticed the park’s tourist center, a Bedouin-style tent on the far side of the parking lot. Walking up, we saw that small group of customers were all smoking arguileh and speaking Arabic. They were playing something by Nancy Ajram. The kids working there welcomed us in Hebrew. We asked them in Arabic whether they knew where the old village was, and found out that they were from Bethlehem, where Maryam’s parents grew up. We laughed about the coincidence, and they tried to figure out if they knew anyone in common. They pointed over to the North, and told us that they thought there were old buildings inside the fence of the kibbutz. We got in the car and drove there on a rough dirt road that ran through vineyards. The car almost got stuck in ruts a number of times, and every time we passed a prickly pear, we got out of the car to look around. A couple times we stole clusters of juicy black grapes from the vines as well.

The kibbutz was not large. We read on a sign that it’d been founded in 1948, probably even before the dust of Beit Jeez had started to settle. We drove around the road, and it seemed almost like a run-down resort, except for the fact that towards the back, we encountered a series of long, low buildings that resembled hothouses. The pungent ammonia smell suggested it was a poultry factory farm, but that was only a guess. Back behind one of the buildings, we found an old cupola, three walls still intact.

We parked the car, and started walking through the weeds. It clearly had once been the shrine of a Muslim saint. It was now in ruins, covered in Hebrew graffiti. A group of Thai workers stepped out from one of the buildings and waved to us, we said, “Shalom,” and waved back. They went back inside.

We noticed two stone buildings on a slight rise, only a couple hundred meters away. They had been completely invisible from the road, but from the shrine, we could see them and even make out the distinctively arched windows and vaulted balconies of Arab architecture. We walked over, stepping through fragrant wild thyme, involuntarily squashing many wild cucumbers, and avoiding the Christ-thorn as best we could. Our pants were soon covered with burrs. More than once, we caught the sweet, caroby smell of wild buckwheat as well. The twilight air buzzed with the wings of insects.

As we got closer, Maryam became more and more excited—it was obvious to all of us that the place was perfect for her scene. As we walked into the courtyard, a lone donkey brayed announcing our arrival.

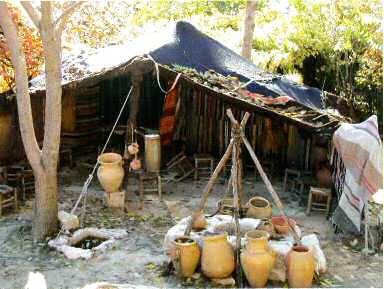

We were astonished to find that these were no ruins. They weren`t even abandoned. Outside, we saw a richly apportioned Bedouin-style tent, replete with small green flags flapping in the approaching evening breeze. Strings of dried peppers adorned the doorways, rustic brooms, axes and shovels leaned against the stone walls. An old iron pot hung on a trapeze over a well-used fire pit. Sprightly chickens chased each other around the courtyard, and goats jumped against each other in their sturdily built pen. Inside, straw mats and pillows covered the floors and walls of the rooms. We saw the remnants of a recently served banquet, still laid out on a low table.

We assumed that this was a tourist exhibit for the kibbutz, an Orientalist venue for holding parties and entertaining foreign visitors. But just then Maryam noticed the equipment, the stacks of booms and lights and the piles of spooled electric cable.

This was a film set. There was no doubting it. The second story balconies were fitted with banks of lights, and a couple of industrial tripods for overhead shots. The donkey continued to bray loudly. He wouldn’t stop.

Soon enough, a couple of men came out of the production truck parked behind the buildings and asked who we were and what we were doing. We replied in English, and then asked whether this was a film set. One of them told us it was. They were an Israeli crew working for an American production company that was making a series of Arabic-language episodes taken from the Bible. This was the set for the segment on Absalom’s rebellion against his father, King David. We asked more questions, and the guy said that if we’d come earlier, we could have met the actors, who were all Arabs. He told us it was no problem if we wanted to come back the next day and talk to the American producers about whatever—about their films, even about how they got permission to use the location. He also told us that it’d probably be easier to speak directly with people at the kibbutz, since they were the ones who owned the property.

When we walked back to the car, we passed by the Thai workers who were sitting nearby drinking tea. Though they invited us to join them, we declined. Maryam was in a hurry to get to the kibbutz office before it closed.